The US electrical grid got its start in 1882, when Thomas Edison erected America’s very first power plant at the Pearl Street Station in lower Manhattan.

One important way Edison’s embryonic grid was simpler than ours is that his customers could only buy power.

Since they couldn’t generate it themselves, there was no need for any mechanism that would allow them to sell electricity back to him.

While it's true that solar power had already been discovered fifty years earlier, the first useable solar cell didn't appear until 1883, just one year after Edison unveiled his power plant.

It would take 70 more years before solar technology was refined enough to make on-site power generation cost-effective.

And almost a full century would pass before the first customers began selling solar energy back to their utility companies in 1980.

Size

The ability to turn your home into a miniature renewable power plant with a simple rooftop solar system isn’t the only way the US power grid has changed. The most salient difference is how much it's grown.

Edison’s started out with a grand total of just 59 customers. Fast-forward to today and the number of Americans drawing power from the grid has grown to almost 150 million.

But, just as your body functions much the same way it did on the day you were born, the basic structure of the US power grid has also remained more or less constant throughout its 140-year history.

Components

Instead of one power plant run by a single company, America now houses 7,700 power plants operated by 330 utility companies with almost 3,000,000 miles of power lines.

Edison’s plant produced electricity by burning coal. And, unfortunately, whether it's coal, oil, or natural gas, burning fossil fuels still produces 60% of the nation’s power, with nuclear providing another 20%.

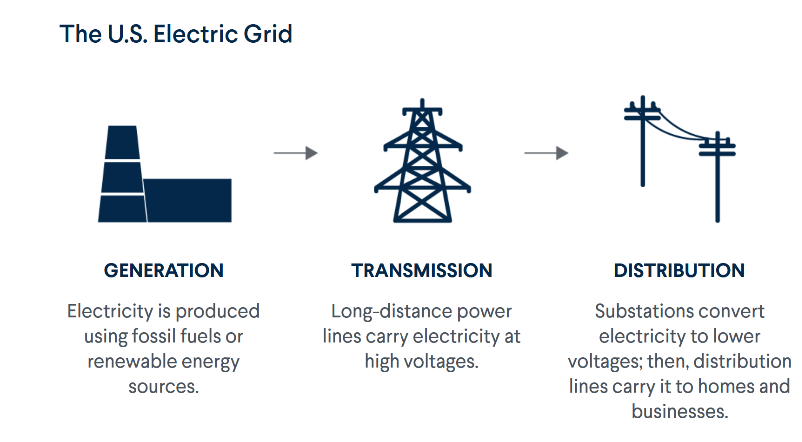

Moreover, though the scope has increased immensely, the steps involved in sending power into our homes pretty much remain the same.

Just as in Edison’s day:

High voltage alternating current (AC) is generated and then sent from power plants to local facilities known as “substations”

The electricity is then converted to a much lower voltage in a process called “stepping down” so it can be safely transmitted to nearby homes and businesses

Miniature rooftop solar power plants

Edison chose alternating current (AC)—which switches direction 60 times a second—instead of direct current (DC) precisely because its voltage is much easier to lower.

And his decision is the reason our appliances run on AC rather than DC.

Solar panels, on the other hand, produce direct current. So, the energy they produce has to be converted to AC before it can be used or—if there’s a surplus—sent back into the grid.

The job of converting solar power from DC to AC is done by devices called “inverters.”

Today we have a multiplicity of power plants—over 3,400 huge behemoths owned by mammoth corporations producing power on an industrial scale plus a growing number of lean and green rooftop solar stations generating clean and renewable energy.

But the basic structure of our nation’s power grid has remained pretty much the same.